Two similar strategies in the note-investing world are often referred to as partials and hypothecation. These techniques can be excellent ways to create a win-win for both parties involved in the transaction.

Selling a note partial or hypothecating a note can each help the note holder to scale their business by providing capital now to reinvest in additional assets for cash flow later. In essence, the note holder can defer profits by using other people’s money to expand their note portfolio for the future. This can be quite powerful.

On the flip side, buying a note partial or providing cash for a note hypothecation can allow the buyer/lender to enjoy a relatively passive and lower-risk stream of income for a period of time. It also allows the partial buyer or lender to diversify across several notes since the amount of money needed for the transaction is less than what would be required to purchase a whole note.

What is a note partial?

A note partial—or a partial note—refers to a portion of a mortgage note. In other words, a partial is a defined number of monthly payments. When a note holder sells a partial to a partial buyer, the buyer is purchasing a certain number of the borrower’s payments, often between 3 and 5 years’ worth. The note seller typically takes the funds paid to them by the partial buyer to go out and buy another note. In essence, the note holder is deferring cash flow now so that they can scale their business for the future.

Typically with a partial sale, the legal ownership and management of the note are transferred to the partial buyer. So, for a certain period of time, the partial buyer has full legal ownership of—and responsibility for—the note. Then, after all of the partial payments are made from the borrower (typically a homeowner) to the partial buyer, the note transfers back to the partial seller, who held the note previously.

Example:

The note holder has a solid, performing note that originally was $100k at 8% for 30 years with payments of $733. The note holder purchased this note for $85k. Since the borrowers have been paying on this note, it now has an unpaid principal balance of $95k and 5 years of seasoning. The note still has 300 monthly payments owed to the note holder, but the note holder would like some cash now to buy another note.

So, the note holder agrees to sell 4 years of payments to a partial buyer for $30k. The partial buyer then pays a lump sum of $30k to the partial seller and begins to receive about $710 per month (after servicing costs). The partial buyer now has responsibility to manage the asset, although both parties obviously have a vested interest in keeping the note performing. The partial buyer is able to make a relatively safe investment with a solid return.

The partial seller takes the $30k and puts it toward the purchase of another asset for their portfolio. They purchase another solid performer with 300 months remaining, paying $350 per month. So, for the next 48 months, the partial seller is receiving $350 per month from both loans combined.

However, after the 48 months, the note holder (partial seller) now has two whole notes from which to receive cash flow: both the note they sold part of to the partial buyer, as well as a new note they purchased with the partial buyer’s funds. At this point, they will still have 20+ years of $1,060 per month in payments to look forward to.

Yes, the note holder gave up about $360 per month ($710 – $350) for 4 years, which was over $17k total, but they will make over $50k in interest alone simply by holding the second note for its duration.

What is note hypothecation?

In the note space, hypothecation usually boils down to the use of an existing note as collateral to create a new loan. As such, the note holder (investor) will take a performing note and offer it up as collateral to then borrower funds from another investor/lender. With a true hypothecation, there is no transfer of ownership of any part of the original note/mortgage.

The note holder again has a strong, seasoned asset that he or she would like to use to obtain cash now without selling the entire note. The note holder can—instead of selling part of the note—use the note as collateral to borrower money from a new lender.

Example:

The note holder again owns a note with an unpaid principal balance of $95k and 300 payments remaining. This time, instead of selling a partial buyer the 48 payments to be paid from the borrower to the partial buyer, the note holder borrowers $30k from the other investor, who has agreed to use the existing note as collateral for a new, 48-month loan with a 8% interest rate to the note holder. The note holder now becomes a borrower and begins paying the other investor approximately $730 per month.

In this scenario, the note does not get assigned to the new lender. Instead, the note holder retains the responsibility of managing the note as well as paying the new lender monthly payments. Ideally, the monthly payment from the note holder to the new lender mimics that of the payment from the borrower to the note holder.

The note holder takes the $30k from the new lender and puts it toward the purchase of a new note. After the 48 months, the end result is similar for both investors as it was in the partial scenario above. The note holder deferred cash flow now in order to scale their business. The second investor (lender) enjoyed monthly cash flow from the note holder for 4 years through a loan backed by collateral.

Hypothecation, like partials, can result in a positive outcome for both investors.

More Key Differences:

With a hypothecation, there can be a bit more flexibility built into the agreement as far as monthly payments to the second lender, as compared to the monthly payments to a partial buyer. Although the payment amounts are often close, a hypothecation payment can be greater than or less than the borrower’s payment.

Further, with a hypothecation, the entire event is between the two investors. The borrower sees no changes or interruptions. With a partial, however, the borrower has to make changes regarding their new lender and possibly their new servicer. This can cause issues for all parties involved.

Caveats:

None of this constitutes legal or financial advice. There are many ways to approach and structure both of these techniques. Further, there could be compliance or tax issues associated with either of these strategies, so be sure to check with your legal and accounting advisors.

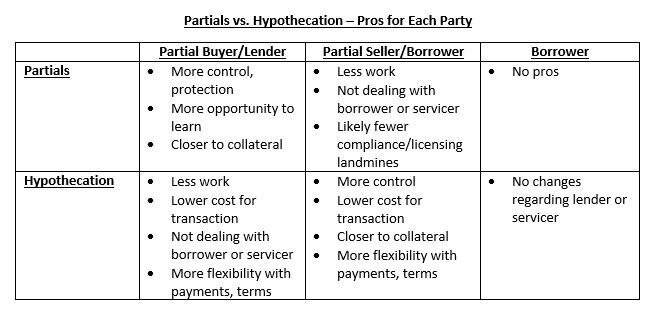

Benefits